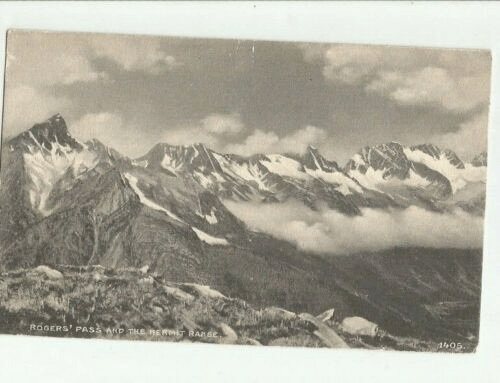

“Such a view! Never to be forgotten!”

These words were written by Albert Rogers in 1881 during his successful attempt to find a route through the Selkirk Mountains for Canada’s first transcontinental railway.

For anyone who has laid eyes upon the vast mountain peaks towering above what has now become part of Canada’s main travel route, the words from the namesake of Rogers Pass are an accurate summary.

The story of Rogers Pass is as unique and demanding as the place itself. Forming a physical barrier to the last steps of uniting a young country, these mountains have challenged and inspired all who have known them intimately.

After the task of building a railway through Rogers Pass was overcome, it began its story as a tourist destination as the striking landscapes and remarkable characteristics began to draw people from around the world soon after the railway was built.

On June 28, 1886, when the railway had just been completed, the first transcontinental train left Montreal, bound for the west coast. Four days later, the train rumbled through Rogers Pass, and on July 4th reached its final destination—Port Moody in Vancouver.

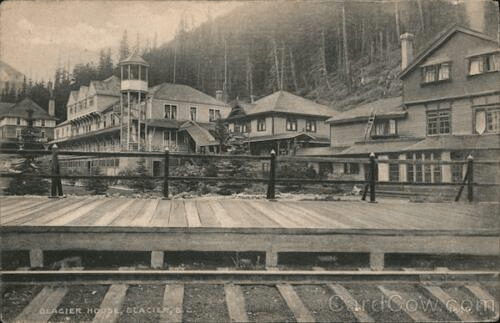

The first tourism facilities in Rogers Pass were built to accommodate train passengers. As dining carts were too heavy for the train to haul up the steep inclines of Rogers Pass, Glacier House was established as a dining hall in 1887.

Built at the base of the “Great Glacier”—now known as the Illecillewaet Glacier, named for the river of the same name, which is an Okanagan First Nations word meaning “swift water”—Glacier House became so popular amongst its visitors that it eventually expanded to a guest house with ninety rooms.

Guest amenities continued to be added until the resort even included a billiard room and a bowling alley. Thus, Glacier House had became the first of the railway’s luxury mountain lodges, which eventually included the Banff Springs Hotel and Chateau Lake Louise.

Those who came to see the “Great Glacier” did not have far to look. Back in the 1880s, the glacier stretched down to only a mile from Glacier House down in the valley. As the Canadian Pacific railway company recognised the tourism opportunities in these mountainous landscapes, they petitioned the government to set aside forest reserves, and Glacier National Park was established at the same time as nearby Yoho National Park.

Along with the famous glacier, the area began to be noted for its brilliant displays of wildflowers in the summertime, and so botanists would crowd the meadows while mountaineers climbed the surrounding peaks.

As a response to the growing interest of mountaineering in Europe, the railway brought Swiss guides into Glacier House in 1897, and promoted them to tourists as providing safe and enjoyable mountain travel. The first recreational mountaineering in North America began in these mountains, and the railway advertised the mountain parks as “50 Switzerlands in one”.

But with big mountains and big snowfall comes big consequences, which had been warned of by First Nations people, but underestimated by the early European explorers. One notable early explorer, Walter Moberly, attempted to ascend Rogers Pass in late 1865, but his First Nations guides “warned him of massive snows which leapt from the mountainsides upon the unwary traveller. They spoke of snow so deep that neither man nor beast could move against it.”1

Although Moberly heeded their warnings, others did not. During the construction of the railway, more and more people began to be buried in avalanches in Canada’s Glacier National Park, and in 1910 a major disaster struck as 58 people were killed by a huge avalanche. And so finally the first avalanche mitigation practices began in Rogers Pass, which involved re-routing the railway and building the Connaught Tunnel through Mount MacDonald.

As Glacier House was no longer on the railway line, and more difficult to access, combined with high maintenance costs, it was closed in 1925. After destructive fires at the railway’s Banff and Lake Louise hotel locations drained much of their investment capital, the caretakers of Glacier House were laid off in 1927. The buildings were looted and vandalized, and subsequently demolished in 1929. The Great Depression then dashed any ideas of rebuilding.

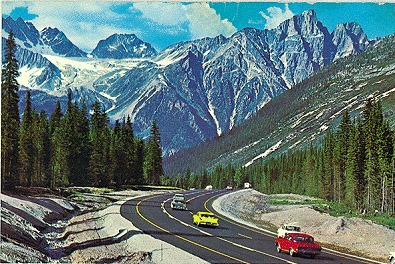

Not long afterwards, the highway through the pass began to be built. As with the railway, the rugged terrain made for hard work, and the highway through the pass took around 20 years to complete. In 1962, it was finally completed. At that time the Trans-Canada became the world’s longest national highway, at 7,821 kilometres long.

This time the avalanche problem was better managed, as elaborate systems were developed to protect the highway. The highway passes through several snowshed tunnels, which eliminate exposure in particularly hazardous areas. Furthermore, features such as earth dams, mounds, and catch basins were constructed in avalanche paths to contain slides. And most notably, Canada’s Glacier National Park is now well-known for having one of the most advanced avalanche mitigation systems in the world, as Parks Canada and the Canadian Forces work together to forecast and control avalanches by shooting them down with Howzer gunners.

The new highway made the pass easily accessible for tourists, who now enjoy Canada’s Glacier National Park year-round as a hiking, climbing and mountaineering destination in the summer, and a world-famous destination for backcountry skiing and ski mountaineering in the winter.

Although Glacier House is now rubble, and the “Great Glacier” has receded to high up on the mountain side, both can still be seen while hiking in the stunning Illecillewaet Valley. Other remnants of history remain stronger than ever—the railway still twists through the mountains alongside the highway, and although they no longer carry passengers, Canadian Pacific Railway trains frequently pass through.

While enjoying a summer evening outside at Heather Mountain Lodge, every now and then you can hear the distant sounds of trains. It’s nice to consider these trains are the reason we are here as the sounds of history echo through the valley.